Combining to Cure: Arcus Founders Talk Strategy and Legacy

There are many examples of productive relationships in science and research. Think of James Watson and Francis Crick, or Marie and Pierre Curie. While these teams inhabited the laboratory, it is rare to find partnerships of this kind straddling the boardroom and bench, especially in modern biopharmaceutical companies. However, the team behind California-based Arcus Biosciences is a perfect example of what a cohesive partnership built on mutual respect can achieve.

Terry Rosen and Juan Jaen, CEO and President, respectively, co-founded Arcus in 2015 with a blank piece of paper and the ambition to develop highly combinable, best-in-class cancer therapies with the potential to be curative.

The overarching vision of “combining to cure” has led to multiple product candidates in the clinic across more than a dozen clinical studies in areas of high unmet need. In seven years, the company has developed six molecules for a range of cancers, two of which are in Phase III trials for non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC).

Arcus, however, is not Rosen and Jaen’s first rodeo. They formed Flexus Biosciences in 2013 to develop small-molecule cancer immunotherapies targeting regulatory T cells. In just over a year, the company was sold to Bristol Myers Squibb for $1.25bn. But Rosen and Jaen clearly had unfinished business with the world of immuno-oncology and co-founded Arcus Biosciences in 2015.

What makes this pair special? The well-known adage that “opposites attract” is true for so many successful relationships, and the opposing yet complementary personalities of Jaen and Rosen are clearly a unique component in what makes their research thrive.

The Perfect Combination

The pair have noticeable commonalities in their backgrounds: both grew up in the city as a product of the public school system and as one of four successful siblings with parents uninvolved in academia or the sciences. Jaen had moved from Madrid, Spain, to a suburb of Detroit to finish his final year of high school. Having met his now-wife on his first day in the United States, Jaen was keen to stay within the state, and, after undergraduate studies in Madrid, he enrolled in the University of Michigan to study for his Ph.D. in chemistry. It was there he met Rosen for the first time.

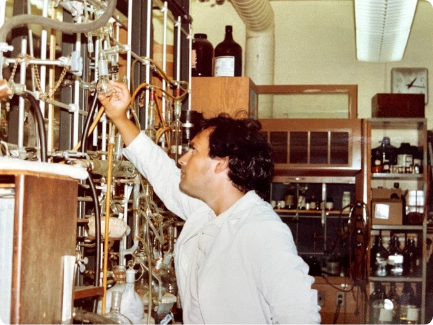

“When I was shown into the lab for the first time, I realized it was already occupied by this young kid,” Jaen recalls. “It was a mess; there were flasks everywhere, he was probably asleep on the desk. There was Terry,” he laughs.

Rosen, a proud Chicago native, had always had a keen interest in chemistry and followed in his older brother’s footsteps to the University of Michigan. Rosen and Jaen shared a project in the lab for the better part of two years before Rosen left to gain his own Ph.D. at Berkeley.

“Juan was the smartest guy in the department,” Rosen recalls, noting that Jaen passed his English exams with higher marks than his US-born colleagues. While Rosen’s self-effacing humor is admirable, it does no justice to the 30-year career he forged in pharma, working in senior scientific and managerial positions at Pfizer and Tularik (later acquired by Amgen).

While Jaen plays the foil to Rosen’s colorful recollections, the pair have a playful dynamic between them that has been forged through nearly 40 years of collegiate respect and friendship. However, underlying this bonhomie is a laser-focused idea of what they want to achieve within drug development, and their ambition has, thus far, been fruitful.

Flexing the Immuno-Oncology Muscle

Rosen and Jaen remained friends through the years while they both established successful careers in big pharma, with the latter holding the position of chief scientific officer and senior vice president of Drug Discovery at ChemoCentryx for seven years, where he led the discovery and progression into the clinic of eight novel immunology drug candidates.

In parallel, Rosen had been successful at Amgen but felt an itch to do something different. With the spark of a concept he wanted to pursue, after seven months of consideration, the idea for Flexus Biosciences was fully formed. He had consulted frequently with Jaen on the core focus of the company and eventually persuaded him to join the team.

Flexus Biosciences was an immunotherapy developer with an indoleamine-2,3-dioxygenase-1 (IDO-1) inhibitor program. In 2015, IDO inhibitors had become hot properties for evaluation in combination regimens with other immunotherapy agents, especially with programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) inhibitors like Bristol Myers Squibb’s Opdivo.

The company used its Agents for Reversal of Tumor Immunosuppression (ARTIS) concept to develop immunotherapies, especially small molecules that target regulatory T cells (Tregs). Just 14 months after starting the company, Bristol Myers spent $1.25bn on the rights to F001287, Flexus’ lead preclinical small-molecule IDO1-inhibitor and an IDO/TDO discovery program.

“The economic outcome was not our intent,” explains Rosen. “It enabled us to start Arcus, more than just financially. Flexus was a perfect storm.” Flexus’ leadership team ultimately determined that it had an obligation to its shareholders to sell the company to Bristol Myers. Rosen explains that the rationale of Arcus is the same as Flexus but this time with a long-term ambition.

The Arcus Ambition

“From day one, we realized that there was a necessity and an opportunity as the industry was starting to combine multiple agents together,” explains Jaen. “In cancer, we saw that we could distinguish Arcus from what other researchers were doing.”

Arcus was not formed around a specific discovery or platform, and its founders had to be very deliberate when selecting biological pathways on which to work. This created both opportunity and pressure for the team, who had to be very exacting in their choices to reduce risk.

“We decided we did not want to chase the latest and brightest scientific publication or discovery,” says Jaen. “There could be a period, maybe years, during which knowledge is constantly changing. We wanted to initially pursue biological pathways that were relatively well understood.”

He describes the company’s strategy for success as a four-legged stool. The programs had to be based on a solid understanding of the biological pathways selected, the development molecules had to be designed with a clear “best-in-class” profile, Arcus had to be in control of all the necessary combination components, including backbone therapies, and, finally, the company would have to invest extensively in the ability to select optimal drug combinations for specific oncology indications, perhaps even customized to specific subsets of patients.

This strategy translated into a number of important tactical decisions. For example, to control the quality of the molecules being discovered and developed, Arcus decided to work with its own labs and extensive development organization. To control the components of the drug combinations, the company decided to in-license and develop its own anti-PD-1 antibody, zimberelimab. To aid in identification of patient subsets that might derive the greatest benefit from specific drug combinations, Arcus made a commitment to translational sciences, which impact every clinical trial in which its drugs are studied.

The early choices made by the Arcus team in executing its strategy are now evident in its clinical pipeline. Arcus identified early on the use of antibodies against PD-1 and anti T-cell immunoreceptor with immunoglobulin and ITIM domains (TIGIT) as backbone therapies for many of its combinations. Other companies have made similar decisions regarding PD-1 and TIGIT; however, where Arcus becomes differentiated from other drug developers is in the unique combinations of small molecules and these checkpoint antibodies that Arcus is able to deploy in the clinic.

Arcus’ research team made an early commitment to developing small-molecule drugs against the adenosine axis. The role of adenosine in suppressing an immune response has been elucidated over decades of research, initially in the field of wound healing and fibrosis, followed by a realization a decade ago that a large percentage of solid tumors rely on the same biology. A tumor can produce adenosine to protect itself from an immune response.

Even though there were several compounds in the clinic when Arcus decided to work on the adenosine axis, Arcus’ researchers realized that the properties of those molecules were not particularly desirable for an oncology drug. “We are not the first company to work on the adenosine axis, but we are the first company to design two different molecules that are custom designed to work in oncology, and bring a significant element of novelty,” explains Jaen.

Etrumadenant, an A2a/A2b adenosine receptor antagonist, is Arcus’ most mature adenosine molecule, currently in Phase II trials as part of novel combinations with Arcus’ anti-TIGIT domvanalimab and anti-PD-1 zimberelimab for patients with lung cancer and in combination with zimberelimab, an anti-angiogenic like bevacizumab and chemotherapy for patients with colorectal cancer. The ambition of these novel combination treatments is simple – to extend survival for more patients.

Pipeline Partnerships

Of course, combining molecules within its proprietary pipeline can only take Arcus’ ambition of combining to cure to a certain point. Partnership deals with AstraZeneca, Gilead Sciences and Japan’s Taiho Pharmaceutical have validated and valued Arcus’ research. The UK-based pharma major has built an alliance that combines the anti-TIGIT antibody domvanalimab with its curative checkpoint inhibitor Imfinzi in Phase III trials for unresectable Stage III non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC). The results of this trial will not only benefit Arcus and AstraZeneca but also long-time supporter and 20% shareholder Gilead, who, at the time of the AZ collaboration, had opt-in rights for this molecule and more.

In November 2021, Gilead and Arcus furthered their pre-existing R&D collaboration when the Big Pharma company exercised options to three Arcus programs, domvanalimab and follow-on AB308, etrumadenant and small-molecule CD73 inhibitor quemliclustat.

At the Cowen & Co. Health Care Conference in March 2022, Gilead’s Chief Financial Officer, Andrew Dickinson, said that excitement around Arcus is not necessarily about any one program. “It’s about all of them and the totality of the quality of science, the quality of the molecules and the quality of the team. They gave us a lot of encouragement and confidence that they’re on the right path, and that collectively we can create value here for both of our shareholders and mutually benefit from it.”

Gilead invested in the Arcus pipeline following early glimpses of the two anti-TIGIT and two adenosine molecules in various combinations.

Continuous Evolution

With one eye on burgeoning skills for the future, Arcus has a nascent commercialization group and is expecting to take a drug to the regulators in the next handful of years. Rosen is keenly aware that many biotech companies falter at this point but knows that Arcus will be able to leverage skills and expertise from partner and shareholder Gilead to intensify its progress. Rosen describes this evolution as “continuous but not random.”

Arcus’ core prowess around small molecule discovery and development is malleable, and with the right surrounding functions, the company could evolve in a myriad of ways, Rosen explains. The sensible step, based upon discovery capabilities that Arcus has built to date, is to move beyond oncology and grow an immunology program as well. Indeed, Arcus has started to work on targets in this space and is actively looking for targets that play to its strengths and technical abilities.

The company is confident in its strategy to date and is now focused on building a long-term independent and commercial organization. “As we look back on the choices we made five or six years ago, every one of them is lining up,” says Jaen. The time is right to look forward to an expanded pipeline and a maturing product offering. “We will maintain a focus on innovation, stay R&D- and patient-centric, and produce clinically significant results that will really make a difference,” says Rosen.

While the path to Arcus may have been curved, the future of the organization is nothing but linear.

RECENT ARTICLES

Combining for Change in Kidney Cancer

While there has been substantial progress in treatment in recent years, even more innovative approaches are needed to improve survival, especially when the cancer is metastatic, meaning it has spread to other parts of the body.

From Paper to Pill

There is opportunity to develop new and potentially improved molecules that block HIF-2α to further improve outcomes.